Mains – 29th Nov 23

INDUS WATER TREATY

Why in news?

- Pakistan ‘unilaterally’ opened an arbitration case at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in January to discuss how the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) should be interpreted and applied.

- India objected, arguing that the questions Pakistan was asking the Court of Arbitration should be resolved by neutral experts rather than the Court of Arbitration because it lacks the authority to do so.

Permanent Court of Arbitration

- It is a non UN intergovernmental institute, established in 1899, to resolve disputes arising out of international agreements between member states, international organisations or private parties.

- It is located in Hague, Netherland. It is the oldest institution for international dispute resolutions.

Indus Water Treaty (IWT)

- IWT was signed in 1960 between India and Pakistan and was brokered by the World Bank, which too is a signatory to the treaty.

- The treaty fixed the rights and obligations of both countries concerning the use of the waters of the Indus River system.

- It gives control over the waters of the three ‘eastern rivers’ -the Beas, Ravi, and Sutlej – to India, while control over the waters of the three ‘western rivers’ -the Indus, Chenab, and Jhelum – to Pakistan.

- The treaty allows India to use the western river waters for limited irrigation use and unlimited non-consumptive use for such applications as power generation, navigation, fish culture, etc.

- Thus by provisions of the treaty 80 per cent of the share of water or about 135 Million Acre Feet (MAF) went to Pakistan while India was left with the rest 33 MAF or 20 per cent of water for its usage.

- It lays down detailed regulations for India in building projects over the western rivers.

- The treaty mandates the establishment of a Permanent Indus Commission (PIC) with permanent commissioners from both India and Pakistan. The PIC is responsible for facilitating cooperation, data exchange, and dispute resolution related to the implementation of the treaty. The commission is required to meet at least once a year.

- The IWT provides a three-step dispute resolution mechanism. In case of any questions or differences, the matter can be resolved through the Permanent Indus Commission. If the issue remains unresolved, either country can approach the World Bank to appoint a Neutral Expert (NE). If there are still disputes after the NE’s decision, matters can be referred to a Court of Arbitration.

A Background of Conflict over IWT

- Indian Decision to Modify IWT

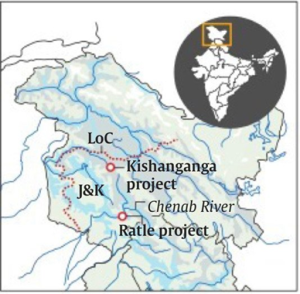

- In January, India announced the desire to modify the 62-year-old IWT with Pakistan, citing what it called Pakistan’s unwillingness to find a solution to disputes over the Kishanganga and Ratle hydropower projects, both in J&K.

- Two hydroelectric power projects, one on the Kishanganga river (a tributary of the Jhelum), and the other on the Chenab (Ratle), have been the subject of a prolonged controversy.

- The World Bank has appointed a “neutral expert” and a chairman of the Court of Arbitration (CoA) regarding the Kishenganga and Ratle hydroelectric power plants.

- India called for modifications to the treaty as per Article XII (3) of the IWT which specify that provisions of the treaty may from time to time be modified for any specific purpose between the two Governments.

- The notice comes as a result of Pakistan’s continuous inaction in enforcing the IWT by repeatedly objecting to the development of hydroelectric projects on the Indian side.

- In January, India announced the desire to modify the 62-year-old IWT with Pakistan, citing what it called Pakistan’s unwillingness to find a solution to disputes over the Kishanganga and Ratle hydropower projects, both in J&K.

- India’s Objection to Arbitration

- India protested Pakistan’s “unilateral” decision to approach a court of arbitration at The Hague in the Netherlands. India raised objections as it views that the Court of Arbitration is not competent to consider the questions put to it by Pakistan and that such questions should instead be decided through the neutral expert process.

The Current Status of Pakistan Initiated Arbitration

- The court determined that it is competent to consider and determine the disputes set forth in Pakistan’s request for arbitration.

- On July 6, 2023, the court unanimously passed a decision (which is binding on both parties without appeal) rejecting each of India’s objections.

Is arbitration useful in the preset scenario?

- IWT provides only some element of predictability

- The IWT parties’ only sane line of action seems to be to pursue legal action in a climate of distrust. However, aside from meeting the countries’ needs for food and energy, it is unlikely to serve the rapidly expanding industrial needs of the two nations.

- The IWT merely offers a sliver of predictability and confidence with relation to the riparian states’ future water supplies. IWT must have flexible procedures that can adapt to variations in the amount of water that is available for distribution among the parties.

Water availability could be affected by climate change

-

- Bilateral water agreements are vulnerable to climate change as most of them include fixed allocation of amounts of water use that are concluded under the assumption that future water availability will remain the same as today.

- The partitioning logic in the IWT does not take into account future water availability.

- With climate change altering the form, intensity and timing of precipitation and runoff, this assumptions regarding the supplies of water for different needs does not hold true.

Way Forward

Inclusion of ERU and NHR into IWT

- This divergent approach can be sought with the help of two cardinal principles of international water courses – Equitable, and reasonable utilisation (ERU) and the principle not to cause significant harm or no harm rule (NHR).

- Although there is no universal definition of what ERU amounts to, the states need to be guided by the factors mentioned in Article 6 of the Convention on the Law of the Non-navigational Uses of International Watercourses 1997, including climate change.

- It is a treaty pertaining to the uses and conservation of all waters that cross international boundaries, including both surface and groundwater.

- Article 6 talks about equitable and reasonable distribution of water by taking into account factors like social and economic needs, population dependent etc.

- The NHR is a due diligence obligation which requires a riparian state undertaking a project on a shared watercourse having potential transboundary effect to take all appropriate measures relating to the prevention of harm to another riparian state.

- Even without its inclusion in the IWT, the ERU and NHR are binding on both countries as they are customary international law rule generating the binding obligation to both parties.

- But the inclusion of these principles in the IWT will ensure predictability to a certain extent.

Need to Revisit the IWT

- The IWT’s fixed allocation of water resources does not account for changing climatic conditions, posing challenges to meeting industrial and agricultural water needs. As water availability fluctuates due to climate change, a more flexible approach is essential to adapt to future conditions.

- Partitioning the rivers between India and Pakistan contradicts the concept of treating the entire river basin as a unified entity. To build sustainable resource capacity, the IWT should encourage a basin-wide approach that optimizes water use for both countries.

- Incorporating ERU and NHR principles from international watercourse law into the IWT is crucial for promoting fair and rational water usage.

Conclusion

- The two countries should use bilateral dispute settlement mechanisms to discuss the sustainable uses of water resources.

- Given the broad contours of the IWT – particularly Article 7 that talks about future cooperation – discussing and broadening transboundary governance issues in holistic terms could be the starting point for any dialogue regarding water disputes.

Explain the key provisions of the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) and its significance in promoting India-Pakistan cooperation. Discuss the need to incorporate ERU and NHR for sustainable water management.

Judicial Pendency

Why in News?

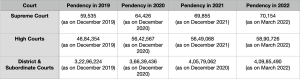

- Pending cases across various courts in the country are moving towards the five crore-mark with an over 4.32 crore backlog in subordinate courts. Supreme Court had 69,766 cases pending before it for adjudication. While there is a backlog of more than 59 lakh cases in the country’s 25 high courts. Out of these, 10.30 lakh cases were pending in the Allahabad High Court — the biggest high court of the country.

- Amongst these cases, there are 29 cases which are pending before the Supreme Court’s Constitution Benches and the oldest case before a five-judge constitution bench has been pending for 31 years now.

- The Centre had set up tribunals and special courts to address the pendency, but cases continue to climb in these forums also. Similar is the case with fast track courts (FTCs) which were set up to dispose of long-pending cases. As of September 2021, over 10 lakh cases were pending in more than 900 FTCs.

Case pending in lower courts

What is a Constitution Bench of the SC?

- A Supreme Court bench with a strength of minimum five judges is called as Constitution Bench.

- It is set up when a significant question of law arises, necessitating interpretation of a provision or provision of the Constitution.

How is a Constitution Bench Formed?

- Article 145(3) of the Indian Constitution says –

- A minimum of five judges need to sit for deciding a case involving a “substantial question of law as to the interpretation of the Constitution”, or

- For hearing any reference under Article 143, which deals with the power of the President to consult the SC.

- The Chief Justice of India, who is also the master of the roster, decides which cases will be heard by a Constitution Bench, the number of judges on the bench and even its composition.

Causes of Judicial Pendency

- Judicial Vacancies & Productivity –

- The current strength is around 20 judges per 10 lakh population which is quite low. The Law Commission in its 120th report in 1987 had recommended 50 judges per 10 lakh population.

- While this reasoning seems intuitive, it is also important to consider the productivity of the country’s judges. To this end, judicial productivity is calculated as the ratio of judges to case disposals per year.

- While empirical evidence on this metric is sparse, one 2008 study suggests that judicial productivity in Delhi district courts is about half of that in Australian courts.

- Budgetary Allocations for the Judiciary –

- The budget allocated to the judiciary is between 0.08 and 0.09 per cent of the GDP. Only four countries — Japan, Norway, Australia and Iceland — have a lesser budget allocation and they do not have problems of pendency like India.

- Poor state of subordinate Judiciary

- District courts across the country also suffer from inadequate infrastructure and poor working conditions, which need drastic improvement, particularly if they are to meet the digital expectations raised by the higher judiciary.

- There is significant divide between courts, practitioners and clients in metropolitan cities and those outside. Overcoming the hurdles of decrepit infrastructure and digital illiteracy will take years.

- Government being the Largest Litigant –

- Intra and inter departmental disputes of branches of governments, states vs centre matters and issues arising and among government and public sector undertakings end up in courts.

- The government, being the largest litigant (40% of the litigation is of the government) should self-motivate itself to use alternate dispute redressal system and approach the courts only as a matter of last resort.

- Poorly drafted orders have resulted in contested tax revenues equal to 4.7 per cent of the GDP and it is rising.

- Court Vacations: The Supreme Court has 193 working days a year for its judicial functioning, while the High Courts function for approximately 210 days, and trial courts for 245 days.

- Low Enforcement of Court Orders: When court orders are not enforced, it leads to additional delays in case resolution. Non-compliance with court rulings undermines the effectiveness of the judicial process.

- New Mechanisms and Litigation: Innovative mechanisms like Public Interest Litigation (PIL) have expanded the scope of cases brought before the courts. While PIL is valuable for addressing public issues, it also contributes to the caseload.

Sharp spike in case pendency in Indian courts has resulted in an increase in the number of undertrials lodged in prisons. An undertrial is a prisoner on trial in a court of law. As per the Prison Statistics-2020, released by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), undertrials accounted for 76% of the total inmates in around 1,300 prisons across the country.

Steps Taken to Reduce Pendency of Cases:

- E-Courts Mission Mode Project: The eCourts Integrated Mission Mode Project is one of the National e- Governance projects being implemented in District and Subordinate Courts of the Country since 2007. It provide designated services to litigants, lawyers and the judiciary by universal computerisation of district and subordinate courts in the country.

- Virtual Courts: Conducting court proceedings through videoconferencing, improving access and speeding up cases.

- E-filing: E-filing allows cases to be submitted electronically over the internet, minimizing physical presence and paperwork. It accelerates case processing and reduces administrative delays.

- e-Payment: Online payment for court fees and fines, minimizing cash transactions and paperwork.

- Interoperable Criminal Justice System (ICJS): Data exchange among justice system components, aiding faster case resolution.

- Fast Track Courts: Dedicated courts for quick case handling, prioritizing backlog reduction.

- Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR): Methods like Lok Adalats, Gram Nyayalayas, and Online Dispute Resolution offer alternate avenues for swift dispute resolution.

- The Centre has introduced a mobile application – Justice App – meant exclusively for judges across the country to help them track how many cases are pending before them.

- The government has also upgraded the judicial infrastructure by introducing Information Communication Technology (e-Court Mission Mode Project) to more and more courts in the country.

- The appointment of judges to the higher courts is frequently recommended by the SC Collegium. For example, in 2021 it recommended the appointment of 129 High Court judges, soon after the appointment of 7 judges to the SC.

- LIMBS (Legal Information Management and Briefing System) by Ministry of Law and Justice – LIMBS provides a low cost web technology access to all the stakeholders involved in a court case in a coordinated way.

Recommendation of Parliamentary Standing Committee on Personnel, Public Grievances, Law, and Justice

- Regional Benches of Supreme Courts: They suggested having courts in different parts of the country so people don’t have to travel far for justice.

- The committee recommended the SC to invoke Article 130 of the Constitution to establish its regional Benches at four or five locations in the country

- Post-retirement Assignments: The practice of post-retirement assignments to judges of the SC and high courts (HCs) in bodies financed from the public exchequer should be reassessed to ensure their impartiality.

- Judges’ Retirement Age: The retirement age of judges needed to be increased since longevity has increased due to advancements in medical sciences.

- More Diversity: The representation of the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, women, and minorities in the higher judiciary is far below the desired levels and does not reflect the social diversity of the country.

- Adequate representation of various sections of Indian society will further strengthen the trust, credibility, and acceptability of the judiciary among the citizens.

- Change Vacation System: Instead of all judges being on vacation together, they suggested judges take time off at different times. This way, courts can stay open more often.

- Declare Assets: The committee said all constitutional functionaries and government servants must file annual returns of their assets and liabilities.

Various Recommendations about Court Vacations:

- 2000: The Justice Malimath Committee, suggested that the Supreme Court work for 206 days, and High Courts for 231 days every year, keeping in mind the long pendency of cases.

- 2009: The Law Commission, in its 230th report had suggested that court vacation be cut down by 10-15 days across all levels of judiciary to help deal with pending cases.

- 2014: The Supreme Court notified its new Rules, it said that the period of summer vacation shall not exceed seven weeks from the earlier 10-week period.

Other Recommendations

- The 112th Law Commission of India report suggested the fixation of the judge strength formula.

- Introducing the All-India Judicial Services (AIJS), after building a consensus within the judiciary.

- The Judiciary should curb the practice of seeking adjournments as a norm rather than an exception.